Path 3

Cultural Impact

“Are fairy tales for children?”

Decide for yourself by listening to the story “Dog and the Sparrow”?

Imagining Fairy Tales

F

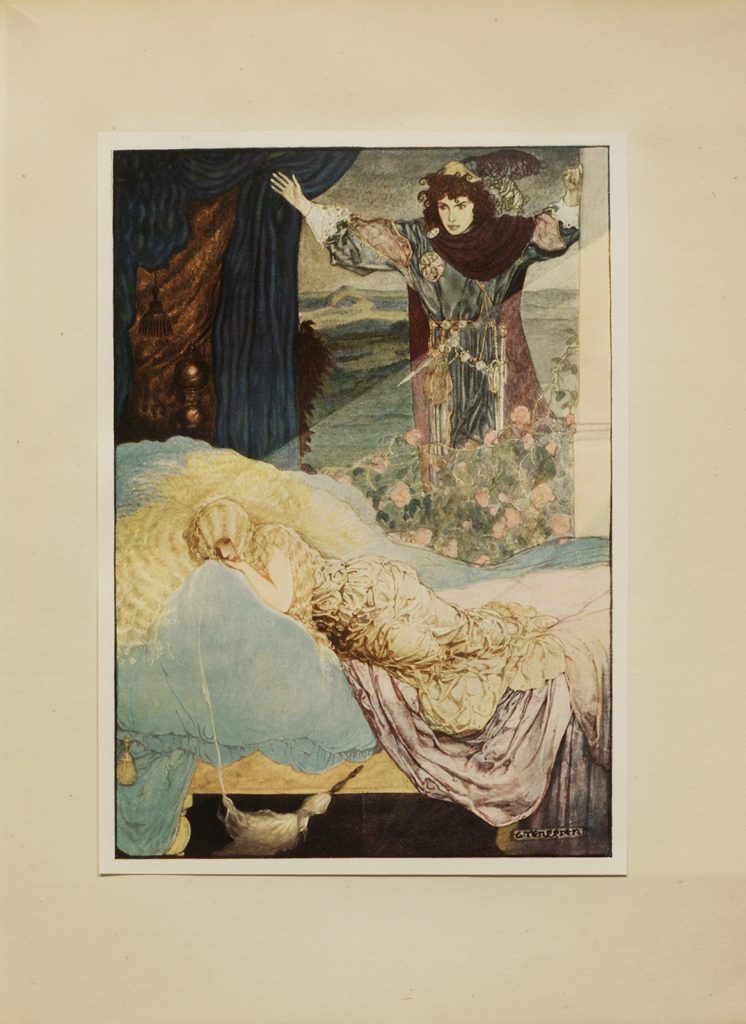

airy tales are more popular worldwide today than ever before. From television series, movies and plays, to opera and dance, from photo series to contemporary art installations, from re-imagined novels to graphic novels, adaptations running the gamut from kitsch to scholarly reinvent fairy tales for today’s culture. Yet these tales remain resilient through interpretations and transformations. While the words evolve slowly, however, images offer a more direct, dynamic response to the texts they accompany. Each new illustrated edition comes with new images, opening a gap between the story in text and in illustration. Within this gap, there is space for questioning and reflecting on the story.

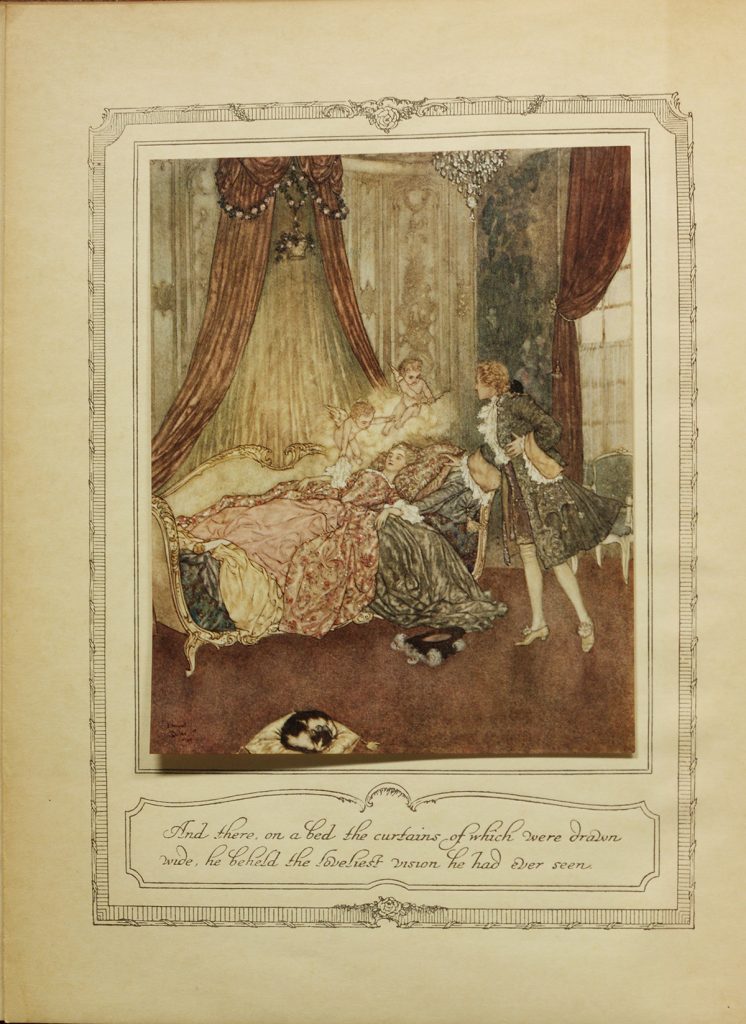

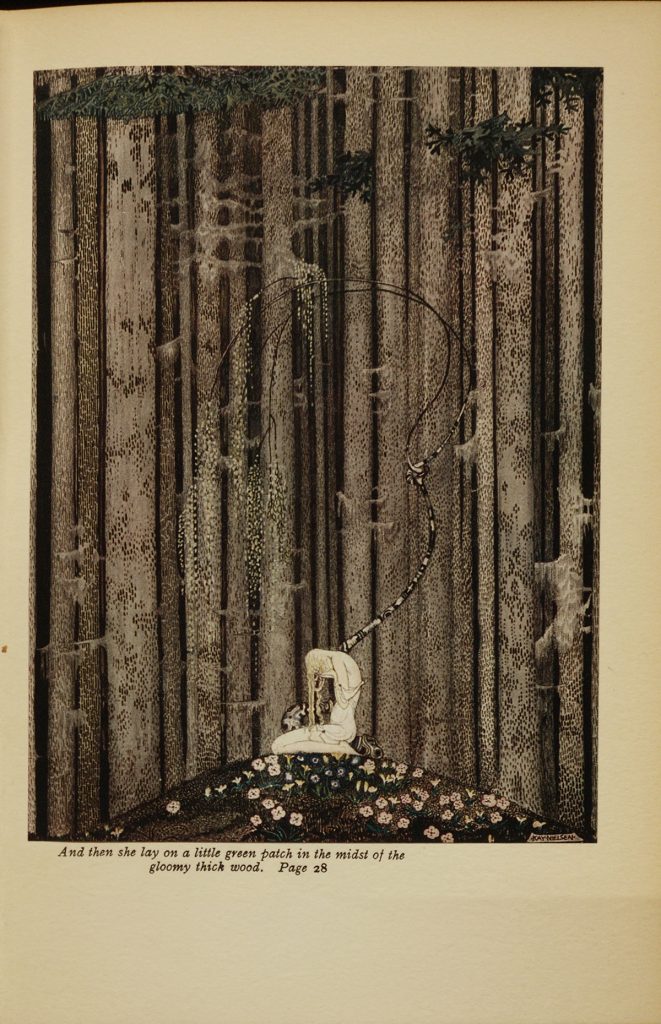

Images re-interpret and re-contextualize the tale, while simultaneously making visible dominant social and cultural preconceptions, thus highlighting how illustrators themselves interpreted and critiqued such tales. Their images, and therefore their perspectives, made lasting impressions on readers. Many of these images depict not only social rules, but the moment the social rule is breached, or the aftermath. It is a visceral message that resonates more instantaneously, such as with the image of the dark and threatening woods through which Little Red Riding Hood must travel to her grandmother’s house. The visual message is immediate and clear: the woods are full of danger, one ought to keep to the path and not let oneself be led astray from it. Interestingly, because the Brothers Grimm originally intended their story collection for other scholars, and not children, they originally saw no need to include illustrations. It was only when influenced by their friend, the lawyer Edgar Taylor, to create an abridged, child-friendly version, that Grimm’s Fairy Tales were first illustrated. The Brothers Grimm were intrigued by the value of illustration for addressing young and old reader alike, while creating further layers of nuance in the storytelling. Yet they were also wary of using illustrations that were too comical or infantilizing, less that dampen the moral imperative of the stories. So from the time illustrated editions of Grimm stories were introduced in the 1890s, illustrations were chosen that added nuance or otherwise complicated the perspective of their texts.

The Golden Age of Illustration

I

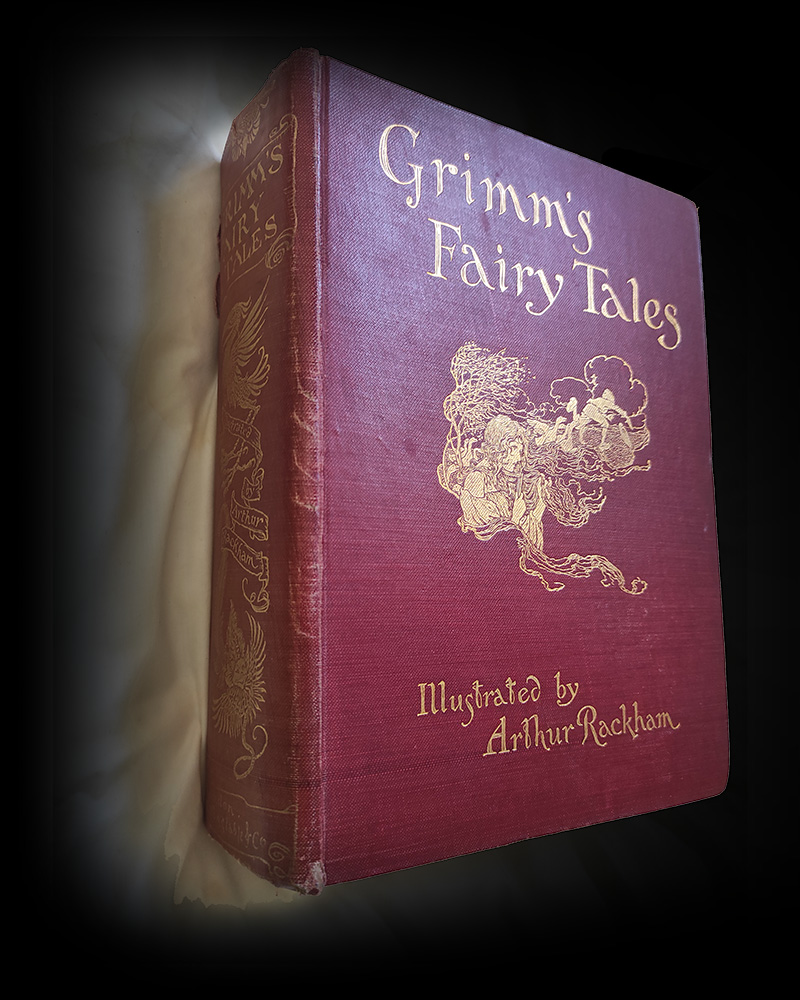

llustrated fairy tales helped readers to imagine fantastical things with never-before-realized detail. Maastricht University is proud to possess 56 richly illustrated fairy tale books from the so-called Golden Age of Illustration, which occurred between the 1880s and the 1930s. This includes the 1923 edition of Grimm’s Märchenschatz: Ausgewählte Kinder-und-Hausmärchen, one of the collection’s best examples of an illustrated Grimm fairy tale book.

The Golden Age of Illustration, which largely centered in England, came about through a confluence of social and economic factors, including increased literacy, more people with expendable income, and improvements in lithography that allowed for the production of cheaper, yet higher-quality, full-color illustrated books. Most illustrators were art school-trained, then went on to related careers such as graphic arts, book and newspaper illustration, banknote design, set design, and painting. The Golden Age of Illustration coincided with the period in design history when Art Nouveau met Art Deco, and the interaction between the two styles is beautifully evident in the books held by Maastricht University’s Special Collections. The majority of these books are first editions in English, issued by publishing houses in the U.K., such as Hodder & Stoughton, Heinemann, and Harrap. Maastricht University’s Golden Age of Illustration Collection belonged to Dutch graphic designer, illustrator, cartoonist, art teacher, author, book cover designer, and art collector Bernhard (Beb) Reith. In 2005, Maastricht University Library acquired Reith’s personal library, containing over a thousand books on art, art history, and drawing, and among them were 56 of the finest works of art ever created for children’s literature. The illustrations will feel familiar to anyone who read fairy tales as a child, or watched the stories played out as animated Disney films. In fact, there are direct links between those Disney films and the illustrated fairy tale books which preceded them.

The Maastricht University (UM) owns more than fifty fairy tale books from the end of the nineteenth to the beginnings of the twentieth century. They are often beautifully illustrated. And they are also invaluable as a source for research and education at our university.

Gustav Tenggren, Kay Nielsen, and Disney

I

n the 2010 animated Disney movie Tangled, a naïve young girl is confined to an isolated tower by her overly protective mother. The girl yearns to leave her secluded tower for an adventure, and escapes with the help of handsome bad boy Flynn Rider. Location: the Kingdom of Corona. Coincidence? A girl locked in quarantine for days on end, in social isolation, and eager to escape her predicament.

Disney loosely based its movie on the fairy tale Rapunzel, included in the 1812 edition of the Brothers Grimm collection. In fact, two Golden Age of Illustration artists were directly linked to Disney. The Swedish-born Gustaf Tenggren illustrated the 1923 edition of Grimm’s Märchenschatz, a copy of which is held by Maastricht University Special Collections. Tenggren had emigrated to the U.S. in 1920, where he continued his book illustration work throughout the 1920s and 1930s. In 1936, he became an illustrator and conceptual artist for Walt Disney Studios. His first major project with Disney was Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (1937). He later collaborated on Pinocchio (1940) and Bambi (1942).

The eccentric Danish illustrator Kay Nielsen first made his name illustrating the children’s story collection entitled East of the Sun and West of the Moon (1914), Andersen’s Fairy Tales (1924), and Hansel and Gretel (1925). Nielsen worked for Walt Disney Studios for four years, from 1937-1941. He contributed illustrations to one of the company’s most iconic and influential films: the 1940 animated musical anthology, Fantasia. Nielsen’s concept paintings were used in the Night on Bald Mountain/Ave Maria sequences. In the years following, he collaborated on many other Disney films, and his designs were incorporated into Disney films made after his death, including The Little Mermaid (1989), based on the story by Hans Christian Andersen.